| home | Aktuell | Lesungen | Biographie | Kontakt |

| Werke & Presse | Übersetzungen | Links | ||

| Presse-Bild | Audio & Video | login |

Die verschluckte Musik

Eine untergegegangene Welt lebt wieder auf, jene elgante, kultivierte Welt, die der rumänischen Hauptstadt Bukarest den Ruf eines "Paris des Ostenns" eingetragen hatte. Dort wächst die Mutter des Erzählers in einer großbürgerlichen Atmosphäre auf und kann scheinbar ohne Sorgen ihre Tage verbringen. Doch bald kündigen sich die Katastrophen des Jahrhunderts an, die auch über diese Familie hereinbrechen werden.

Hallers Erzählkunst ist eindrucksvoll, glänzend und dicht wie realistisches Erzählen im späten neunzehnten Jahrhundert. Äusserste reflektiert und hier ganz Kind seines eigenen Jahrhunderts, zeigt er dabei die Mittel der Illusionierung, die ihm als Autor zur Verfügung stehen, um Szenen und Personen eines verblichenen Universums vor Augen zu führen.

Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Jahrbuch der Allgemeinen Deutschen Zeitung, 2011

Dr. Markus Fischer

Literarische Bilder von Bukarest in Christian Hallers „Trilogie des Erinnerns“

Der Schweizer Schriftsteller Christian Haller, 1943 in Brugg geboren, hat mit seinen drei Romanen „Die verschluckte Musik“ (2001), „Das schwarze Eisen“ (2004) und „Die besseren Zeiten“ (2006) ein monumentales Generationsepos vorgelegt, das den Vergleich mit den großen Familien- und Gesellschaftsromanen des 20. Jahrhunderts nicht zu scheuen braucht. Für die in der „Trilogie des Erinnerns“ zusammengefassten Romane wurde der vielseitige Autor 2007 mit dem renommierten Schillerpreis und ein Jahr zuvor mit dem Aargauer Literaturpreis ausgezeichnet.

Schauplatz dieser drei Generationen umspannenden Familiengeschichte ist nicht allein die Schweiz, sondern, vor allem im ersten Roman „Die verschluckte Musik“, auch Rumänien, insbesondere die Hauptstadt Bukarest. Dieses Faktum liegt in der Lebensgeschichte der Mutter des Ich-Erzählers begründet, die als Dreijährige mit ihrem Bruder und ihren Eltern nach Bukarest zieht, wo ihr Vater im Jahre 1912 zum Direktor einer Baumwollfabrik ernannt wird. Die Mutter verlebt nahezu ihre gesamte Jugend in der rumänischen Hauptstadt, bis die Familie im Jahre 1926 endgültig Rumänien verlässt. Der Abschied aus Rumänien bedeutet für die Mutter nicht nur den Abschied von der Familienvilla in der Strada Morilor, dem geschützten Raum ihrer Kindheit und Jugend, sondern auch den Verlust einer großbürgerlichen Lebensweise, die sie in ihrem späteren Leben niemals wieder genießen wird.

Dieses Unwiederbringliche einer leuchtenden, ja gleißenden rumänischen Vergangenheit wird zum Signum, ja zum Stigma im Leben der Mutter, dem sich auch der Sohn, der Ich-Erzähler der Romantrilogie, nicht entziehen kann. Im Jahre 1997, mehr als siebzig Jahre nach der Ausreise der Mutter aus Rumänien, als die Mutter in der Schweiz bereits in einem Pflegeheim lebt, aber in ihren wachen Momenten immer noch von ihrer rumänischen Vergangenheit schwärmt, reist der Ich-Erzähler für eine Woche nach Bukarest, um das Haus in der Strada Morilor aufzusuchen und seiner Mutter von den Orten ihrer Kindheit zu berichten.

Für einen Leser, der Bukarest kennt und mit den rumänischen Verhältnissen vertraut ist, aber auch für jeden anderen unvoreingenommenen Leser ist Christian Hallers Romantrilogie aus mehreren Gründen interessant. Erstens, weil hier Bilder der rumänischen Hauptstadt von großer schriftstellerischer Sensibilität, sprachlicher Artistik und realistischer Lebensnähe entworfen werden; zweitens, weil diese Bilder immer in historischer Brechung und zeitversetzter Parallelisierung dargeboten werden, wobei ein Erfahrungsraum eröffnet wird, der nahezu das gesamte 20. Jahrhundert umspannt; und drittens, weil diese erzählerisch kunstvoll gewobenen Rumänienbilder, diejenigen vom Beginn und diejenigen vom Ende des Jahrhunderts, miteinander kontrastieren, sich ständig wechselseitig kommentieren und zum Teil auch gegenseitig konterkarieren.

Besonders interessant ist die ungewöhnliche Perspektive, aus der der Ich-Erzähler die rumänische Hauptstadt betrachtet und die natürlich von der Idealisierung Bukarests durch die Mutter entscheidend mit geprägt ist. Bukarest ist für ihn nicht nur die Stadt hinter dem Eisernen Vorhang, eine kommunistische Metropole des Ostblocks, etwas letztlich nicht Vorzeigbares, ein „Unort, wohin man nicht ging, woher man nicht kam“ (Christian Haller, Trilogie des Erinnerns, München 2008, S. 667), sondern Bukarest ist für ihn zugleich und in weit größerem Maße ein unerreichbares Ideal, ein verlorenes Paradies, das vor allem im Reich der Phantasie existiert.

Nachdem die Mutter mit ihren Eltern als junge Frau in ein Schweizer Dorf gezogen ist, träumt sie sich immer wieder in eine imaginierte und imaginäre Bukarester Welt zurück. Die Dorfstraße wird zur Fürstenstraße, auf der Kaleschen, Cabs und Landauer dahin rollen, die sie die neue Schweizer Lebenswirklichkeit vergessen lassen: „Man grüßte mit einem Kopfnicken zu einer kreuzenden Kutsche hinüber, bewunderte Madame Volvoreano oder Duca oder Ghica, die statt eines Hutes einen Schal aus Venedig luftig um den Kopf geschlungen trug, entsprechend der Vorliebe Königin Marias, die man in ihrem Automobil zu sehen hoffte, schätzte eine kurze Stockung vor Riegler oder Capşa, um vielleicht ein bekanntes Gesicht im Innern der plüschigen Cafés zu entdecken, und wenn man dann am Palatul Regal und dem Athenäum vorbei beim Hotel Athénée Palace angekommen war, so konnte man sich entscheiden, weiter und hinaus zur Şoseaua Kiseleff zu fahren, wo einmal im Jahr das Blumenfest stattfand und die Chaussee zwischen Gärten und Villen zu den Seen führte, oder eben wieder zu wenden und den Corso durch die Calea Victoriei neu zu beginnen, durch Wagen- und Menschgedränge zurück zum Platz vor dem Nationaltheater, so einige Male, bis man genug gesehen hatte und genug gesehen worden war“ (S.168f.).

Die Reise des Ich-Erzählers nach Bukarest im Jahre 1997 ist zugleich die erinnernde Suche nach der Vergangenheit seiner Familie, insbesondere nach dem Leben der Mutter und des Großvaters. Der Ich-Erzähler sucht diejenigen Orte und Plätze in Bukarest auf, die er schon von Kinderzeiten her gut kennt, zwar nicht aus eigener Anschauung, jedoch aus Erzählungen der Mutter, aus Fotoalben oder von Postkarten, die die Mutter aufbewahrt hat. So hält der Ich-Erzähler eine Postkarte mit einer Ansicht des Bukarester Platzes Sfîntu Gheorghe in Händen, die der Großvater am 30. Juni 1912 an die Großmutter geschrieben hat, bevor sie mit ihren beiden kleinen Kindern dem frisch ernannten Fabrikdirektor an seine neue Arbeitsstätte in Rumänen nachfolgen sollte. „Sfîntu Gheorghe/Lipscani: Das ist der Centralpunkt, nach welchem man von uns aus per Tram fährt, um nach den verkehrsreichen Plätzen zu fahren“ (S. 44), so hatte der Großvater geschrieben, und auf den Tag genau fünfundachtzig Jahre später steht der Ich-Erzähler just an der Stelle, an der der Großvater einst gestanden und in die Strada Lipscani hineingeblickt hatte. Während dem Großvater sich die berühmte Handelsstraße Bukarests jedoch als Ort geschäftigen Treibens und farblichen Reichtums dargeboten hatte, als städtischer Raum „warm und gelb wie Mais, erfüllt von einer Gemächlichkeit und sommerlichen Nonchalance, vielleicht ein kleines Paris“ (S. 50), so erlebt der Ich-Erzähler diesen Ort zwei Generationen später völlig anders: „Ich blickte über breite Fahrbahnen, suchte Großpapas Perspektive zu finden, und sah in die Strada Lipscani hinein, den Blick halb verstellt von einem Kioskgebäude, und es war keine ‚romantische Passage’, in der Stände und Läden an einen ‚bunten, orientalischen Basar’ erinnerten, wie ich in einem Reisebuch gelesen hatte, sondern eine ärmlich zerrüttete Straße mit schäbigen, halb leeren Läden, Baulücken, Ruinen und aufgerissener Pflasterung, ausgesaugt von Entbehrung, als hätte alle Anstrengung auf etwas außerhalb ihrer selbst gerichtet werden müssen – wie in einem Krieg“ (S. 157f.).

So erlebt der Ich-Erzähler die rumänische Hauptstadt, in die seine Mutter niemals mehr zurückgekehrt ist und die er selbst nun zum ersten Mal in seinem Leben besucht, als doppelbödige Parallelwelt, als permanentes Vexierspiel, bei dem sich Gegenwart und Vergangenheit, eigenes Erleben und Familienerinnerung beständig abwechseln und dabei unablässig ineinander gleiten. Dementsprechend versucht der Ich-Erzähler, die von seiner Mutter ins Fürstliche gesteigerte Calea Victoriei, den mondänen Promenier- und Flanierboulevard Bukarests, den „Corso der Eleganz und Verschwendung“ (S. 170), mit den Augen der Mutter zu sehen: „Ich wollte die Calea Victoriei großartig und glanzvoll sehen, doch selbst mit dem besten Willen und einer beschönigenden Phantasie gelang mir dies nicht: Die Straße war ausgezehrt und ausgeblutet, ein trister Korridor des Mangels, grau von Teer und Staub, durch den der Verkehr sickerte. Die Passanten trugen abgenutzte Kleider, und ihre Bewegungen waren müde oder steif von unbewussten Durchhalteparolen. Die Geschäfte hatten wenige und zufällige Waren anzubieten, eher aus Hinterhöfen zusammengetragen als einem Überfluss und Luxus entnommen, und unter dicken Schichten kalkgrauer Vernachlässigung entdeckte ich Reste einstiger Pracht und Urbanität, eine Fassadenfront, ein einzelnes Gebäude, die ich von alten Fotos oder aus Erzählungen kannte, doch sie wirkten wie zufällige Überbleibsel zwischen der drängenden Hässlichkeit der Blocks“ (S. 174f.). Obwohl es dem Ich-Erzähler nicht gelingt, die Calea Victoriei im Sinne der Mutter zu ‚leisten’, um ein Wort Rilkes zu gebrauchen, ruft er sie, die Schwerkranke, vom Bukarester Telefonpalast aus in der Schweiz an. „Und ich spürte ihre Erschütterung. Sie lag im Spital, in einem dieser Vierbettzimmer, abgetrennt vom Alltag, und ihr Sohn meldete sich aus der Vergangenheit, vom Ort ihrer Kindheit, wo sie die beste Zeit ihres Lebens verbracht hatte. Ich begriff, dass ich in dem Moment durch meine Reise zu einer Figur ihrer Seele geworden war, zu einem Boten, der ihr Nachricht aus den eigenen inneren Räumen bringen würde und sich in den Bildern eines mit dem eigenen Sterben beschäftigten Menschern bewegte“ (S. 183). Auf die Frage der Mutter, wie ihm Bukarest gefalle, antwortet der Sohn auf anrührende Weise: „Es ist wunderbar, sagte ich, so überzeugt, wie es mir möglich war und auf eine später noch zu entdeckende Art auch stimmte. Ich mag die Stadt, ich liebe sie! Der Triumph teilte sich selbst über diese Distanz hinweg durch die Telefonleitung schweigend mit. Sie war erlöst, sie hatte sich nicht getäuscht, es gab Bukarest, es gab die Calea Victoriei noch, und sie waren genauso geblieben, wie sie die Stadt und ihre Prachtstraße erinnerte, nämlich wunderbar“ (S. 183f.).

So lässt sich insbesondere der erste Teil der „Trilogie des Erinnerns“ nicht nur als Familienroman lesen, sondern auch als Bukarest-Roman, der eine Fülle von urbanen Schauplätzen wie einen Bilderbogen aufblättert und diese in unterschiedlichster Weise kommentiert. Dabei kommt Familiengeschichtliches wie Zeitgeschichtliches, Stadthistorisches wie Kunsthistorisches gleichermaßen zur Geltung. Die Bronzeplastik „Die Läufer“ (1913) von Alfred Boucher, die früher vor dem Athenäum stand und heute an der Calea Victoriei neben dem Wirtschaftsministerium aufgestellt ist, wird in den Augen des Ich-Erzählers zum Sinnbild atemloser Gehetztheit und überstürzter Flucht angesichts einer hässlichen und verlogenen Lebenswelt. Der Bukarester Bahnhof gerät ins Blickfeld des Erzählers, der Park Cişmigiu, der Stadtfluss Dîmboviţa, der See Herăstrău, das Restaurant Carul cu Bere, die Piaţa Unirii und neben vielem anderen immer wieder auch die Bukarester Hunde: „Bukarest ist voll von Hunden, es gibt bestimmt zwei- bis dreihunderttausend davon in der Stadt, sie sind überall, und es ist ihnen längst nicht mehr beizukommen. Sie sind ein Erbe des bürgerlichen Bukarest, das noch aus Häusern mit Gärten bestand und in dem jede Familie ihren Vierbeiner hatte. Als Ceauşescu den Stadtkern zerstörte und die Leute in die Wohnblocks zwang, durften sie keine Hunde mitnehmen. Die Tiere blieben in den Straßen zurück, verwilderten, vermehrten sich“ (S. 141).

Am Ende des Romans „Die verschluckte Musik“ gelangt der Ich-Erzähler schließlich zur Villa in der Strada Morilor, in der die Mutter groß geworden ist. Die Villa liegt im Süden der Stadt, am Rande des jüdischen Viertels und unweit des Schlachthofs, wo im Januar 1941 Legionäre der „Eisernen Garde“ ermordete Juden mit der Aufschrift „koscheres Fleisch“ an Fleischerhaken aufgehängt hatten. Auch dies kommt in Christian Hallers Romantrilogie zur Sprache, die Familiengeschichtliches in einen welthistorischen Horizont zu rücken weiß und die das Schicksal der Familie zu geschichtlichen Ereignissen wie dem Ersten Weltkrieg, dem Zweiten Wiener Schiedsspruch, der Deportation und Vernichtung europäischer Juden, dem Zweiten Weltkrieg und seinen Folgen wie auch der Rumänischen Revolution von 1989 in Beziehung setzt.

Neu Zürcher Zeitung, 13. 11. 2001

Andrea Gnam

Rückkehr zur Schau der Dinge

Christian Hallers Roman über ein entschwundenes Bukarest

«Es schwankt» - mit dieser Feststellung beginnt undendet der Roman «Die verschluckte Musik» des 1943 geborenen Schweizer Autors Christian Haller. Sie steht geradezu paradigmatisch über einem Werk, das sich einer Erinnerung annimmt, die nicht die unmittelbare eigene Vergangenheit ist. Die literarischeRekonstruktion einer zwar fremden, aber doch aus Familienerzählungen präsenten Zeit ist eine Hommage des Ich- Erzählers an seine Mutter.

Altersverwirrt und sterbenskrank möchte sie sich der Existenz der Stadt ihrer Kindheit vergewissern. Als Tochter des Schweizer Direktors einer Textilfabrik hatte sie vor und nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg eine grossbürgerliche Kindheit im alten Bukarest zugebracht. Ihretwegen fährt der Sohn nach Bukarest. Er soll ihr berichten, ob diese Stadt, wie so vieles andere, nur in ihrer Vorstellung oder doch auch im wirklichen Leben existiert. Das Bukarest, das ihm aufgegeben ist zu suchen, ist zweifellos für den Sohn der «jenseitige Seelenraum der Mutter». Wie aber als Erzähler sich einem Ort und einer Zeit nähern, die beide imaginär bleiben werden und dennoch konkretes Leiden an der Vergangenheit zeigen - hierin der «verschlucktenMusik» gleichend, welche der verwirrten Mutter aus ihrem eigenen Leib entgegenzutönen scheint?

Szenen eines verblichenen Universums

Hallers Erzählkunst ist eindrucksvoll, glänzend und dicht wie realistisches Erzählen im späten neunzehnten Jahrhundert. Äusserst reflektiert und hier wieder ganz Kind seines eigenen Jahrhunderts, zeigt er dabei die Mittel der Illusionierung, die ihm als Autor zuVerfügung stehen, um Szenen und Personen eines verblichenen Universums vor Augen zu führen. Visuelle Medien wie Photographie und Film, die dem Leser als private und zugleich zeitgeschichtliche Vermittler eines Gedächtnisses zur Verfügung stehen, schwankende Zeugnisse einer entronnenen Zeit, führen zunächst wohlbekannte Erinnerungsbilder vor Augen. Sie beschwören eine Vergangenheit, wie sie das Familienalbum zuwegbringt. Korrekt gekleidete Gestalten, liebenswürdig und anrührend steifbeinig, findet man hier. Der Erzähler hat den Ort ihrer Sehnsucht, wie er dem Leser mitteilt, «blau koloriert». Trügerisch sind diese Photographien im Hinblick auf die Erinnerung selbst, vor die sie sich schieben. Auf einer Photographie ist von der Mutter nur noch eine Schleife zu sehen. Der langen Vorbereitungen überdrüssig, mit der ihr Vater Haus und Familie standesgemäss in Szene setzen will, hat sie sich hinter einem Baum versteckt. Etwas anders verhält es sich mit den Erzählungen der Mutter, die beim Sohn eigene Bilder, ein «Kopfalbum» evozieren, das nicht minder präsent ist wie das Familienalbum. Besonders nachhaltig aber sind die akustischen Bruchstücke, die den Sohn - unverstanden - die dunklen Seiten der Geschichte der so urban wirkenden Stadt ahnen lassen: Ein rätselhafter obszöner Fluch und der Klang des rumänischen Wortes für Schlachthaus, in dem später entsetzliche Verbrechen an Juden stattfinden werden, legen sich über das heitere Bild.

Gewebe und Gerümpel

Um den allmählichen Rückzug der Mutterausdem Leben zu zeigen, die sich schon als junge Frau in die Vergangenheit geflüchtet hat, setzt der Erzähler eine alteingeführte literarische Metapher, die des Textes als eines Gewebes, opulent und einleuchtend in Szene. Die Mutter erzählt von einem Ornament, das auf Bändern und Stoffen, auf Häusern und Kacheln das alte Bukarest durchzieht. Dem kleinen Mädchen wird es zum magischen Inbegriff für die so faszinierende wie in ihrer Kultur doch fremd gebliebene Stadt. Wie in einem von der Zeit still gestellten Genrebild sieht der Sohn, selbst noch ein Kind, die Mutter selbstvergessen über aus Bukarest mitgebrachte Stoffe gebeugt. Das Gewebe mit den Fingerspitzen berührend, scheint sie vor den Augen des ratlosen Jungen in die Heimat der Vergangenheit zu entschwinden.

Der erwachsene Sohn, der das heutige, von Ceausescu rücksichtslos umgestaltete Bukarest besucht, ist hingegen mit einer prosaischen Gegenwart konfrontiert. Zur literarischen Beschwörung des alten Bukarest muss er auf andere Erinnerungsbilder aus seinem privaten Bilderarchiv zurückgreifen: etwa auf den Eindruck des Fremden bei seiner Ankunft in Bangladesh. Dass er beruflich Paläontologe ist und in seinen Bericht Auszüge aus einer Forschungsarbeit über den Aufbau der Feder einflicht, die zwar motivisch lose mit der Familien- geschichte verknüpft werden, ist in dieser feinsinnigen Studie über die Konstruktion der Erinnerung fast überflüssig. Allerdings motiviert es jene langen Satzverknüpfungen, die flugs von der Gegenwart in die Vergangenheit springen. Gerne auch über die Generationen hinweg schlagen sie durchaus gelungene, schwindelerregende Bögen zur Erd- und Kulturgeschichte. Die Passagen über das heutige Bukarest, über die Wunden, welche die Ceausescu-Ära hinterlassen hat, geben dem Buch eine zusätzliche Dimension, die weit über die private Erinnerungsarbeit und die literarische Reflexion hinausgeht, und bewahren es vor bodenloser stilistischer Artistik. Wie eine Rückkehr zu einer Schau der Dinge selbst scheint es dann auch, wenn der Sohn in einem Raum voll alten Gerümpels ein mit eigenen Augen gesehenes Symbol erkennt (es mag an Walter Benjamin erinnern), das den Zustand der Mutter, aber auch den der kollektiven Erinnerungsarbeit ins Bild setzt. Im wie ein Wunder noch vorhandenen grossväterlichen Haus in Bukarest lässt er sich den Salon zeigen. Von der derzeitigen Besitzerin, einer ehemaligen Funktionärin des Ceausescu-Regimes, wird er als Abstellkammer genutzt. Er habe die Empfindung, in die innerste Welt der Muttergetreten zu sein, schreibt der Erzähler, «in ihr altes brüchiges Hirn, alles war dort wie früher, der Plafond, die Wände und Tapeten, nur gealtert und jetzt voll gestellt mit Stücken, die sich angesammelt hatten, die man nicht weggeben oder aufgeben wollte und die nun gestapelt hier lagen, mit der Zeit immer mehr in Unordnung geraten. Und ich stand nur einfach da, in dieser verfallenden Welt, sah und hatte gefunden und war selbst wie erlöst.»

Christian Haller: Die verschluckte Musik. Roman. Luchterhand-Verlag, München 2001. 268 S., Fr. 32.80.

Corina Crisu

Bucharest Revisited:

Transcultural (Post)memory in Christian Haller’s Swallowed Music

A Genre Bending Novel

Written in German and intended for a Western readership, Christian Haller’s

Swallowed Music (2001)1 expands the boundaries of Western literature by referring to

an unknown, often misrepresented area of Eastern Europe. Unlike in other stories

about migration, the movement here is not from East to West, but from West to East,

and back again. The novel is not written by an Eastern European immigrant who tells

the West about his country, but by a Westerner who embraces Romania as a mother

country. Reconstructing its past Weltanschauung and making it accessible to the

Western mind, the novel acquires the unique ability of describing a complex, multilayered

country. From a terra incognita – an unreadable map of meaning – this country gains specificity, taking shape in its most concrete details.

The work of a Swiss with Romanian affinities, Swallowed Music can be

intertextually linked with other fictional pieces about dislocation and migration by

Romanian immigrant authors, such as Herta Müller, Domnica Rădulescu, Andrei

Codrescu, Gabriela Melinescu and Carmen Bugan – who write in a foreign language

targeting their message to a Western audience. All these writings do not promulgate

dominant patterns of representation, dichotomic views that perpetuate notions of

Western superiority and Eastern inferiority. These writers’ views are more nuanced

and their perceptions of Romania – infused by autobiographic experience – explore in

depth the cultural and historical factors that have shaped the country’s worldwide

image.

In this context, Haller’s Swallowed Music comes as an unexpected, atypical

novel: written by a foreigner, it contains insider’s information about Romanian

traditions, customs, habits of mind – all described in minute detail, all presented from unexpected angles by someone who has experienced the country first-hand and seen it

with a double pair of eyes. In particular, the novel speaks to us about Bucharest, about

the transformations in its urban configuration and the social and psychological

mutations it undertakes from age to age. Through the technique of distancing, of

correlating two spatial points by moving the narrative focus between Romania and

Switzerland, the image of contemporary Bucharest is placed into perspective –

attaining a transnational dimension. With the eye of an insider-outsider, Haller

discovers a palimpsestic city, with a rich, multi-layered history beyond its actual

surface defaced by communism. Bucharest changes diachronically as we travel from

an old Bucharest, as it was in 1912 (a space where old values were still preserved in

an increasingly demented world threatened by imminent war), to a more

contemporary, post-1989 Bucharest (a city of most striking contrasts, where unique

gems of the interbellic architecture can be identified among communist

monstrosities).

Swallowed Music is more than a complex novel of inter-war atmosphere with

poignant autobiographic accents. In Jan Morris’s words, this is “a genre bending”

book, one which subtly combines fiction and journalism, musical leitmotifs and

scientific observations, photographic collage and documentary close-ups (19). The

novel is not written in chronological order, but follows the non-linear thread of

memory and its fragmented variations, with their hauntingly repetitive and circular

movements. This shattering of the initial story into pieces creates the effect of

simultaneity, so that the past and the present are skilfully juxtaposed. Each chapter

contains references to objects, postcards, photographs, and diaries – that have the

function of “chronotopes,” relating distinct spatio-temporal levels and re-creating

mentalities of a bygone era (Bakhtin 250).

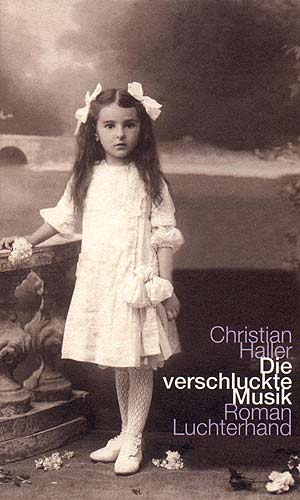

This emphasis on a bygone era can be detected by comparing the front covers

of the German and Romanian editions. One can notice here the publishers’ different

perceptions of the novel, as well as their strategies for preparing their readers’

expectations. In both cases, the publishers chose old photographs with a sepia tint,

giving a clue to the reader about the novel’s emphasis on the past.

The German edition features a young girl in the 1920s, wearing an impeccable

white dress, who adopts the rigid posture imposed by the photographic studio and

whose scrutinizing, wondering look seems to reach beyond the frame of the picture;

in the background, like a premonitory sign, a stormy sky is dramatically tumbling

down. In the Romanian edition, the picture shows a carriage drawn by two white

horses on Calea Victoriei in the 1920s or 30s. With its fin de siècle architecture and its

trottoirs crowded by elegant people, Calea Victoriei is an emblematic image of

Bucharest, le petit Paris, as it used to be called at the time.

In a complementary way, the two images speak about two essential aspects of

the novel: its female character (the German edition) and its main setting (the

Romanian edition). Both aspects will be discussed in this article, laying stress on the

osmosis between self and city and the trauma of separation, on the avatars of an urban

space permanently reshaped by memory. Starting from the outside, from public

spaces such as boulevards and squares, and moving to more intimate descriptions of

private spaces, and even further, to the warm proximity of emotionally loaded objects

– Haller makes us see the present through the lens of the past, depicted in nuances of

yellow, the colour that captures the multifarious reflections of remembrance.

Postmemory and Traumatic Displacement

In Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory, Marianne Hirsch uses

the term “postmemory” to designate that special type of remembrance belonging to

the children of the Holocaust victims; the post-war generations that have never known

the horrors of the genocide experienced by their parents are still haunted by their

parents’ past:

Postmemory characterizes the experience of those who grew up dominated by narratives that preceded their birth, whose own belated stories are evacuated by the stories of the previous generation, shaped by traumatic events that can be neither fully understood nor re-created( 22).

The second generation cannot fully grasp the enormous impact of the traumatic events

on their parents, striving to understand the meaning of past stories and photographs, to

bridge the gap between unspeakability and articulation.

As Hirsch observes, “postmemory” can become a useful tool for discussing

not only Jewish history, but also “other cultural or collective traumatic events and

experiences” (22). The impact of traumatic events transmitted from one generation to

another is also evident in the case of those emigrants who forcefully have to leave

their country. While the first generation has to pass through the painful uprooting

process, the second generation can still feel its consequences, re-experiencing the

acute feeling of displacement and the permanent state of in-betweenness.

The nuanced idea of “postmemory” can be applied to Haller’s novel, when

discussing the narrator’s perspective and the way he tells the unusual story of his

family. Of wealthy German origin, the S. family arrives in Bucharest in 1912, Herr S.

(the narrator’s grandfather) being the director of the Lemaître textile factory. After a

period of smooth accommodation and prosperous life in Bucharest, they are forced to

leave the country, in 1917, during World War I. After two years spent in Switzerland,

they return to Greater Romania as to a homeland, only to leave it forever in 1926. The

easygoing spiritual richness of the time spent in Bucharest provides the family

members with an ideal for their future lifestyle. Emotionally anchored in the

Romanian past, they experience an inner exile in Switzerland, where they do not feel

different from other emigrants. Notably, the family has to leave Romania twice – the

first departure (in 1917) serving as a temporary prefiguration of the other permanent

displacement (in 1926).2 Determined by unforeseen socio-political circumstances,

both departures are traumatic experiences for the family.

In Switzerland, Herr S. goes bankrupt after investing his fortune in the textile

industry at a time when it had no future. The trauma of displacement and the painful

loss of social status deeply affect the family members, who feel that their world “is

shaking” (9).3 Herr S. retreats in a world of his own, finding refuge in painting, while

his wife struggles to keep the family together. In her turn, their teenage girl, Ruth,

cannot fathom the abysmal change in her life, longing to bridge the gap between her

past and present homes.

In a fragmented narrative that shifts all the time between past and present, the

narrator knows only parts from his family’s story. He has to read between the lines of

his mother’s recollections, to confront the “holes” in her past created by trauma

(LaCapra 41). His own limited (post)memory denies him full access to her story, to “a

knowledge so partial that it borders on denial, a revelation so incomplete that it

obscures” (Herman 1).

Thus, Hirsch’s idea that the second generation has limited access to the

memory of its precursors can be found here, where the unnamed narrator can only

partially re-tell his family’s story. Recounting a twice-told story, the narrator guides

himself by his mother’s recollections and his grandfather’s photographs. Memory as it

comes to the reader is a second-degree memory – or postmemory – as the narrator

detects beyond their recollections something deeper, a past way of life which cannot

be fully regained.

Born in Switzerland, the narrator learns from early childhood to discern

beyond the plain facts of daily reality the sophisticated rhythm of his mother’s

thoughts – “the swallowed music” – evoking, invoking again and again the place of

her own youth: the capital of Romania as it was between 1912 and 1926.4 Almost

seventy years later, in the early 1990s, the narrator travels back to Bucharest to discover the deeper meaning of his family’s story, to initiate a Proustian quest for a

lost prenatal time.5

In a desperate fight against the gradual amnesia caused by Ruth’s

Alzheimer’s, the narrator wants to go back to a place once loved by his mother and

find a gate of communication with her. He explains to another character in the novel:

I did not come here for professional reasons… My mother spent her adolescence here in

Bucharest; now she is an old lady, who is ill and not able to travel. I wanted to come back here in her place and find those areas of Bucharest where she spent her youth (56).

His own profession as a palaeontologist becomes emblematic here, as he has to dig

beyond layers of significance and to rebuild a lost image starting from a simple

element, a relic from his mother’s past.

À la recherche du temps perdu, the narrator enters the fictional reality of a

place that is continuously reinvented – half-real and half-unreal, half-utopian and

half-dystopian – a place of return, which is never the same with the one of departure.

Calea Victoriei: Broadening the Swiss Horizon

In Swallowed Music memory (or postmemory) takes a transcultural turn. As the

characters’ lifestyle abruptly changes by crossing the borders from East to West, they

desperately try to preserve the memory of the past – to maintain it in material or

spiritual forms.

An urban, bourgeois atmosphere is recreated by Ruth in her Swiss home, so

that a Biedermeier box becomes a symbolic “shrine,” an enclosed, sacred space where

precious memorabilia are displayed. Full of photographs, daguerreotypes, feathers,

and jewels, the Biedermeier box is “a little exhibition of one’s soul,” where each

object preserves its authenticity (34). In Mikhail Bakhtin’s terms, these memorabilia

items can be seen as “chronotopes,” having the metonymic function of reconstructing a past reality in the present environment.6 Similarly, in the grandparents’ home in

Basel, another “shrine” exists, on the graceful chest of drawers made of rose wood;

the strange, ornate pots, which are “irradiating a warm, protective feeling,” the brandy

gourd whose colours suggest “the fading light of torrential rain,” are objects touched

by a patina of age, by “a dirt that domesticates… and gives depth” (165-66).

Visual images intersect with olfactory and tactile ones, in order to recreate a

whole ambience. By holding an ashtray, the narrator is transported back in time,

feeling the lazy comfort of a Romanian home, the sound of muffled steps over Persian

carpets, and the sweet smell of Egyptian cigarettes (166). In another instance, Ruth’s

repeated gesture of caressing the soft roughness of an old piece of cloth represents a

way of “feeling at home through her touching” (135).

This is the world that the narrator’s mother and grandparents once loved, a

Romania of the mind, lost and never fully regained. Their hidden sorrow, selfeffacement,

and retreated life disclose their inability to adapt or be assimilated in the

new country. They raise the children (the narrator and his brother) keeping the old

traditions and rituals of making tea and coffee, and cooking Romanian recipes. Years

later, when arriving in Bucharest, the narrator re-tastes these dishes, discovering the

lost flavour of “Southern sensuality” in a bowl of sour soup (ciorbă) or marinated

peppers (201).

The narrator’s biculturalism is revealed by his way of negotiating a space for

his double belonging through constant movement between the different, but not

antithetical, poles of his existential axis. Listening to his mother’s stories, looking at

old photographs, the narrator learns from early childhood to think via associations

connecting various aspects of his family’s existence by means of an emotional logic.7

This simultaneity of perception enables him to “inhabit one place,” but to “project the

reality of another” (Seidel ix).

Inter-war Bucharest is always present in the narrator’s mind, broadening the

horizon of the small Swiss village where he lives. Re-shaped under the Swiss sky,

Bucharest becomes a city of contrasts, of snowy winters and hot summers, of lazy

afternoons spent at leisure, behind the white curtains, while listening to the sellers’ incantations coming from outside: “ardeiridichidelunăcartofi” (83). Ruth remembers a

multicultural city, tolerant to foreigners, in which Romanians lived together with

Germans, Jews, and Romani. She remembers the family’s usual route in a horsedrawn

carriage, along the Dâmboviţa River, to Sf. Gheorghe Square, to Athénée

Palace, down on Calea Victoriei, and finally to Herăstrău Park.

Since “roots precede routes,” as James Clifford famously stated (3), the

narrator’s sense of belonging to the Romanian cultural space gives meaning and

direction to his daily itinerary:

I was carrying inside me a grand street, a royal street, and I let it unroll inside me like a carpet in the middle of the village, among small houses, to the chocolate shop and the Tea-Room, to the centre and inside the school (149).

Going to school becomes a self-centred experience, as the narrator imagines himself

walking down Calea Victoriei, the “royal street,“ populating it with luxury hotels,

chic cafes, and boutiques. He isolates himself from the others in order to imagine the

world that is lying behind the Iron Curtain, translating an Eastern European reality

into a Western context. Facing the East in the West,8 he acknowledges his affinities

with Romania, and defines himself, just like his mother, as “a true emigrant” (149).

“I have nothing to do with these morons,” Ruth declares, distancing herself

from her Swiss neighbours, whom she considers rural and unmannered, in spite of

their prosperity (202). Adopting urbanism as a way of living, she criticizes the

contemporary Western lifestyle for its individualistic thinking, its lack of refinement

and contact with the past. Ruth herself wants to maintain a certain kind of etiquette by

transmitting to her children the inter-war good manners. A German neighbour in

Bucharest, the stylish Madame Megiesch – “the chocolate mother,” as Ruth used to

call her – becomes the model of a true lady (120-21).

In an intriguing way, the narrator spiritually identifies with his mother, while

saying very little about his Swiss father, an absent figure in the novel. His mother’s

preoccupation with the past transforms him irrevocably into a “strange mutant,

incapable of living in the real world” (Makine 195). Hence, the narrator’s double

perception of space that makes him an exile, someone who has “the power to live here with one’s feet on the ground,” but also there, “miles away in his imagination”

(Jankélévitch 253, my translation, my italics).

Bucharest – A Place of Return

In his well-documented book The Vanished Bucharest, the Romanian architect

George Leahu reconstructs the image of old Bucharest as it was before communism,

indicating that “millions of memories, of recollections, still in our minds and souls,

are now nothing but shadows of real things so heartlessly crushed and pushed away

by the bulldozer” (120, my translation). Leahu points to the disastrous consequences

of communism: a ruthless regime that destroyed the organic growth of a city,

disfiguring it. These “shadows of real things” come to life in Haller’s novel, where

the characters keep re-memorating them.

In the 1990s, when the narrator arrives in Bucharest, he is helped by two

Romanian acquaintances, Sorin Manea (a former dissident) and Monsieur Uricariu9 (a

former communist) to explore different facets of the city. He has a feeling of déjà vu:

the crowded streets remind him of Bangladesh and the sparsely furnished interiors of

Italy after WWII (42, 65). However, his mother’s recollections and his grandfather’s

photographs do prevail as authentic perceptions, giving depth to what would have

otherwise been a tourist’s superficial impression. “I wasn’t going to find out anything

about this city, except a fugitive, exterior impression,” he confesses (100). At the

intersection of his family’s memory and his actual experience, Bucharest is not

stereotypically presented as a one-dimensional city, an image frozen in time, but as an

evolving reality.

Before going to Bucharest, the narrator’s simple act of buying a map and

(re)tracing the plan of the city represents a confirmation, a proof of the real existence

of the place – of the correspondence between his mother’s recollections and the

printed text. The narrator is amazed by the image that is taking shape in his mind

“with such a huge power of penetration” and by the “re-memorated feeling” of living

in “a past that precedes [his] past” (92). Under the magnifying glass, following his

mother’s shaky hand, he repeats an old route, immersing himself in the scorching heat of the Romanian summer, allowing time to stop for a moment on Morilor

Street/”Strada Morilor” where his mother spent her youth (91).10

The real map and Ruth’s mental map do not completely overlap, the latter

preserving a lost configuration of the city, of its old places – now wiped out,

forgotten, or renamed. Faithful to her past and struggling not to lose her memories,

while suffering from a merciless illness, Ruth refuses to acknowledge any change and

modernization. She advises her son: “You can take the horse drawn tramway, number

1, to Sf. Gheorghe Square;” to which the narrator replies: “Now there is an

underground station” (94).11

Through temporal oscillation, urban space is constantly remapped in the

novel. Bucharest is no longer a place contained in one map. Beyond its modern,

eclectic appearance, lies another city still visible to the naked eye. The ever-changing

urban patterns created here through flashback techniques provide a rhizomatic type of

map – similar to Deleuze’s and Guattari’s concept of a map having a multiplicity of

entries and intermingling lines that “cut across a single structure” and “are susceptible

to constant modification” (12). This map – which is permanently readjusted and

acquires new dimensions through time – should be seen as a “rhizomatic (‘open’),

rather than as a falsely homogeneous (‘closed’) construct” (Huggan 409).

Haller’s rhizomatic mapping of Bucharest makes the reader aware that the

present aspect of Bucharest is the result of Ceauşescu’s program of urban planning

called “sistematizare” (systematization). It consisted in the demolition and

reconstruction of urban space, with the goal of turning Romania into a multilaterally

developed socialist society. By employing techniques of de-/re-territorialization that

juxtapose past and present images, the novel makes us reconsider urban space. In

significant episodes, the narrator walks through contemporary Bucharest and searches

for remnants of the past; beyond Casa Poporului – this monstrous construction

designed and nearly completed by the Ceauşescu regime, which required demolishing much of Bucharest’s historic district – the narrator wanders through a maze of blocks

of flats, thinking of the vanished churches, houses, and gardens.

Exploring Bucharest becomes the essence of the novel itself, which can be

discussed using a whole “rhetoric of walking” (De Certeau 388). In parallel scenes,

the walks of the narrator intersect with those of his grandfather, their steps creating

“intertwined paths” that “give shape to spaces” and “weave spaces together” (De

Certeau 386). The novel thus privileges movement over stasis, journeying over

fixation, travel functioning as a form of reconnection with a place of origin, half-lost

and half-preserved. Progression in space paradoxically comes to imply regression in

time.

In the summer of 1912, the narrator’s grandfather sets foot for the first time in

a torrid Bucharest, with the certainty of having found his “Centralpunkt”/“central

point,” in a city meant to be a refuge for his “settled, ordered existence, bearing the

mark of wealth and nobility” (40, 43). Following in his grandfather’s footsteps,

holding in his hand an old postcard, the narrator identifies with his grandfather: “I am

standing, exactly after eighty five years, in the same place where my grandfather

stood and I feel in the corners of my mouth his smile” (45). In spite of the broken

pavement and the coat of dust that covers the city, the narrator recognizes that

“yellow light,” that unequalled colour which he has known for a lifetime, “without

having seen it before,” like the “echo of a perfume emanated by the word Romania”

(47).

The grandfather arrives in Bucharest where the traditions of the Belle Époque

are still preserved and where, to quote another character, “one could still live

excellently” (46). By emigrating to Romania and choosing it as an adoptive country,

the grandfather desperately tries to maintain the principles of an aristocratic lifestyle

threatened by the inexorable forces of history: the xenophobic restrictions imposed on

foreigners, the growing anti-Semitism, and the beginning of World War I.

In his elaborate photographs where every detail is highly staged, the

grandfather – the old fashioned gentleman with the eye of a painter and the mind of

an engineer – wants to transfigure reality and reconstruct an epoch that is falling into

desuetude. By sending these compositions to his relatives in Cologne, he lays accent

on his aristocratic status.12 His perfectionist manner, betrayed by his incessant readjustment of the photographic image, reflects his desire to correct a social reality and

to tell the others about his prosperous life in a stable world.13

The grandfather’s photographs – these material images that have survived the

passage of time – have a priceless value for the narrator, becoming an integral part of

his life story. As Marianne Hirsch notices, “family pictures depend on such a

narrative act of adoption that transforms rectangular pieces of cardboard into telling

details connecting lives and stories across continents and generations” (xii).

Having an inseparable spatio-temporal dimension, the photographs can also be

seen as “chronotopes,” as organizing centres “for the fundamental narrative events of

the novel” (Bakhtin 250). In his later walks through the city, the narrator uses these

photographs as reference points, which give him a sense of orientation and help him

find the house on Morilor Street, “die kleine Villa”/“the little villa” with a garden

(32). Situated in the south of Bucharest, the street runs parallel to the Dâmboviţa

River, connecting the centre of the city with the periphery. This is a liminal zone, an

imprecise boundary between the visible city, delineated by the glamorous route daily

taken by the family in a luxurious carriage, and its invisible part, where the gypsies

used to live, where the children were not allowed, and where “the end of the world”

started (33).

As the narrator later discovers, Morilor Street is also close to the

slaughterhouse where in January 1941 a massacre of Jews took place during the

National Legionary State which initiated a campaign against the Jews culminating in

a pogrom when many Jews were arrested, tortured, and killed. The close proximity of

the slaughterhouse makes the narrator juxtapose two traumatic memories: that of the

Jew’s massacre and that of his family’s forced departure. Only one or two hints can

be found in the novel about the massacre; still, the silence of the other characters,

their change of attitude, and their attempt to keep the narrator from going there, all

testify to the depth of these unspeakable events.

Photograph in hand, groping his way through a labyrinth of derelict houses,

the narrator looks for his mother’s old house, refusing to turn back, to deny the past, to forget. His meandering walk and endless peregrination14 in search for a forever receding

place point to his desire to grasp a past image – one that is infinitely deferred

and constantly displaced. When the narrator encounters a group of gypsy children

who fiercely guard their territory, not allowing him to pass, the photograph becomes

his visual passport entitling him to enter this forbidden zone. His impression is that of

crossing a threshold and going inside “a dislocated part of memory” (69):

For a moment, I had the impression that I had entered the photograph taken by my grandfather in October 1912,… that I had sneaked inside the icon of our family and I was amazed that something really existed in that place that I had contemplated again and again in the album when I was a child: I was inside my mother’s secret world… I was standing in front of a house which had represented for her a lifestyle and which existed in reality (254).

This miraculous passage from memory to reality (and back to memory) is surprising

here, as the narrator seems to enter an imaginary world, stepping behind “this curtain

beyond which [his] mother had retreated every so often, leaving [him] only with

suppositions” (254).15

Seen together, the photograph and the real image acquire fresh layers of

association. The image portrayed in the photograph becomes tangible, each object

taking shape as the narrator touches it: the iron fence (that replaced the old wooden

one, which was stolen in 1917), the ornaments on the walls (never renovated, now

having the consistency of wax, of “lifeless skin” (255)), and the unforgettable colour

of the vieux rose stove. Transposed through the colour of old photographs,16 each

object seems to gain a life of its own, while simultaneously vanishing back into a past

that inflects the present. The actual owners of the house, the Filips, confirm the

authentic nature of the photograph, tying the knots of the story and telling the narrator

how things changed after Ruth’s departure, how the whole area became derelict,

during World War II, when many foreign entrepreneurs left the country.

A recurrent question nags at the narrator, making him doubt the validity of

those decisions that change one’s life irrevocably and that produce an unbridgeable

fissure:

Then why did they leave, and why did they end up in Switzerland, in this country that is so lucid? I’ll never find out. The truth is that they could never adjust, my grandfather lost his fortune, was forgotten in his room, and the S. family, who was present long ago in this garden, looking so proud in front of the camera, lost itself and the aristocratic life it had here (261).

Returning to Switzerland, the narrator finds out that it is too late “to find Ruth

S. in her own past” (24), that she has already lost her memory. In the hospital room,

the hidden “radio” inside her womb has stopped broadcasting; there is no music, no

news about the S. family. “I only remember having memories,” she confesses (267).

The novel has a cyclic structure, as it begins and ends with the same words – “it’s

shaking” – suggesting the fragility of the existential condition marked by the passage

of time. In the last scene, a glass is shaking in Ruth’s hand on the point of falling and

shattering, symbolizing the irreversible loss of memory.

Ultimately, it is the swallowed music, the inner music that the narrator can

now hear. He inherits his mother’s spiritual legacy and in his turn tells her story to the

others – reminding us that “every piece of writing is in essence a testament,” a

precious possession passed on to the reader (Derrida 69).

1 Die verschluckte Musik, München: Luchterhand Literaturverlag, 2001. All the quotations in this article are my translation. Swallowed Music is part of a trilogy, together with The Black Iron (Munich: Luchterhand, 2004) and The Better Times (Munich: Luchterhand, 2006) – two other novels that continue the family saga, focusing on the post-war period.

2 During World War I, when Ruth and her parents leave Romania driven away by poverty and hunger,

they arrive in Vienna, where the situation is even worse than in Bucharest. Later on, they are forced to

spend the winter in a ghetto in Linz, being considered “emigrants from Romania (an enemy country)”

(192). Very little is known about the time spent in the ghetto. Ruth, who is only eight years old, does

not remember – or refuses to remember – more than childish games, divagating to unessential details.

Unable to articulate an unspeakable experience, she proves to be an unreliable source of information

for the narrator. This is why the narrator tells the story by quoting from a historical document: the

report of an Englishwoman, Rahel Silberling. She writes about their daily tasks in the ghetto; she also

mentions sharing a room with Rahele Berkowicz and Onkel Medel – a Jewish couple that has close

connections with the S. family. In Ruth’s story of detention, there is embedded another tragic story:

that of Onkel Medel and his persecution for being a Jew. Remembering the time spent in the ghetto in

Linz becomes equivalent with speaking about the Mendel’s painful experience deportation to

Bucovina: “we couldn’t understand the horror… we never talked about it” (195). The narrator records

only the silence, the gap opened by the abyss of pain, “a darkened place” inaccessible to him (195).

3 In the first scene of the novel, the S. family leaves Romania, in 1926. During their voyage on the

River Danube, from Giurgiu to Vienna, each family member remarks that the ship “is shaking,”

metaphorically pointing to their own existential fragility (9).

4 Swallowed Music does not simply refer to the obsessive symptoms of a person who has Alzheimer’s

and hears a continuous monologue. Situated in her womb, this music is Ruth’s most important

possession, her memory of the past. Drawing us inside Ruth’s mind and its repetitive thoughts, this

music marks the passage of subjective time, which eludes the irreversible linearity of physical time.

5 There is a thematic similarity between Haller’s novel and Andreï Makine’s Le Testament Français :

both novels can be read as half-autobiographic documents about Bucharest and Paris, as well as textual

quests for cultural inheritance. If, in Haller’s novel, the mother brackets the Swiss reality to remember

Romania, in Makine’s novel, Charlotte, the grandmother who lives in Siberia, evokes the Parisian

lifestyle at the beginning of the century. Reading attentively the faces of these two women, one can

sense beyond their physical differences, the infinitesimal lines of inner resemblance. In their daily

activities, their gestures mirror one another, as they open photo albums, caress old objects, or read the

faded pages of letters.

6 Bakhtin observed that the “chronotope” is not restricted to the analysis of the novel and can be

applied to other forms of art, so that it can be applied in particular to memorabilia items, which have

strong connections with historical and personal events.

7 This way of thinking is conjunctive, rather than disjunctive; it functions according to the pattern “andand,”

rather than “either-or,” thus correlating his present experience with that of his ancestors (Miroiu

11, my translation).

8 This paraphrases the title of an important collection of articles Facing the East in the West: Images of

Eastern Europe in British Literature, Film and Culture (Eds. Barbara Korte, Eva Ulrike Pirker and

Sissy Helff. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2010).

9 Alias Dragomir in the Romanian edition.

10 Significantly, Ruth describes a city with a pattern, with a recognizable design that structures the

place geometrically, suggesting order and giving it coherence: “The slabs in the garden on Morilor

Street had a pattern… little crosses and holes, and this pattern was similar to that on the curtains in the

living room and dining room, to that on my mother’s blouses, which she had been wearing since we

came to Bucharest… Even the house had a pattern like that, and one day I was to discover these

patterns… on every street, on people’s faces” (71).

11 As Ruth gets older, she retreats into her own world, alienating herself from others. Her alienation is

evident in her total refusal to acknowledge change in the outside world, in what Jean Améry called “a

difficulty of understanding an unknown order to signs” (108).

12 In the photograph taken by the grandfather, Ruth, his daughter, is not present. Desiring to capture the

geometric order of the house and garden, he forgets about his daughter, who restlessly moves out of the

frame. Ruth’s absence in the photograph is symbolic, pointing to her own effacement in the story.

13 Throughout the novel, there are references to the forgotten art of dyeing feathers – another way of

carefully (de)composing the present, of masking the harsh reality with illusory dreams.

14 The word’s etymology is significant here, relating the idea of movement to that of discovering a

place with a foreign eye: from Latin, peregrinari, from peregrinus, foreigner , from pereger, being

abroad : per-, through + ager, land .

15 Rodica Binder remarks that the drawn curtain has “a protective function,” giving Ruth the necessary

isolation for her privacy, but also serving as a soft, fluid barrier that “does not allow her memories

beyond the windowsill” (Binder 286, my translation).

16 In an interview, Haller talks about the “emotional zones” of his “Romanian biography,” pointing that

“the word ‘Romania’ was associated with the word ‘yellow,’ not a bright yellow, but a dark one.

Something similar to tobacco. But also something oriental. A diffuse light” (see Vlă dă reanu,

http://www.ziaruldeiasi.ro/suplimentul-de-cultura , visited on 02.02.2013, my translation).

Works Cited:

Améry, Jean. On Aging: Revolt and Resignation. Trans. John D. Barlow.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael

Holquist. Ed. Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981.

Binder, Rodica. “Postfaţă: Iubirea şi literatura – Două antidoturi împotriva

amneziei/Postface: Love and Literature – Two Antidotes against Amnesia.”

Swallowed Music. Trans. Nora Iuga. Iaşi: Polirom, 2004. 283-89.

Clifford, James. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century.

Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

De Certeau, Michel. “The Practice of Everyday Life.” The Blackwell City Reader.

Eds. Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002. 383-93.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and

Schizophrenia. Trans. B. Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press, 1987.

Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Trans. Gayatri Spivak. Baltimore and London:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

Haller, Christian. Die verschluckte Musik. München: Luchterhand Literaturverlag,

2001.

---, Muzica înghiţită. Trans. Nora Iuga. Iaşi: Polirom, 2004.

Herman, Judith. Trauma and Recovery. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory.

Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Huggan, Graham. “Decolonizing the Map.” The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. Eds.

Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. London and New York:

Routledge, 1999. 407-11.

Jankélévitch, Vladimir. 1974. Ireversibilul şi nostalgia/The Irreversible and the

Nostalgia. Trans. Vasile Tonoiu. Bucureşti: Univers Enciclopedic, 1998.

LaCapra, Dominick. Writing History, Writing Trauma. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 2001.

Leahu, George. Bucureştiul dispărut/The Vanished Bucharest. Bucureşti: Editura Arta

Grafică, 1995.

Makine, Andreï. Le Testament Français. Trans. Geoffrey Strachan. London: Hodder

and Stoughton, 1997.

Miroiu, Mihaela. Convenio. Despre natură, femei şi morală/Convenio. About Nature,

Women and Morals. Bucureşti: Alternative, 1996.

Morris, Jan. “Critic’s Choice.” Financial Times (29 November 2008): 19.

Rushdie, Salman. Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism, 1981-1991. London:

Granta Books, 1991.

Seidel, Michael. Exile and the Narrative Imagination. New Haven: Yale University

Press, 1986.

Vlădăreanu, Elena. “Christian Haller Face Cunoscută România cititorilor din

Elveţia”/”Christian Haller Introduces Romania to the Swiss Readers” (23

February 2009): http://www.ziaruldeiasi.ro/suplimentul-de-cultura, (visited on

02.02.2013).